Is Rudolf Steiner Christian?

The question “Is Rudolf Steiner Christian” can best be answered this way. He wasn’t for the first 35 years or so of his life, but he became one as his path of independent clairvoyant research led him, via a profound “crisis of the soul”, to clairvoyantly perceiving the crucial importance of the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ at Golgotha – apparently for days or even weeks on end. Only after this event did he (consciously) become a Christian.

Only after his ‘conversion’ – which took place in the final part of the 1890s – did Steiner begin to speak about his clairvoyant and spiritual views. His first esoteric lectures took place in the autumn of 1900, before a Theosophical gathering in Berlin. Until that moment, while already clairvoyant as a boy, and already a prolific writer in Germany in the 1890s, Steiner limited himself to non-esoteric subjects, clouding everything in general philosophical language.

The sequence of this is important, because (1) Steiner only became a Christian after the ‘clairvoyant evidence’ led him to that conclusion, and (2) because it is often claimed that Steiner “started from Christianity and then deviated from that to develop his own esoteric worldview”. In fact, it’s the other way around!

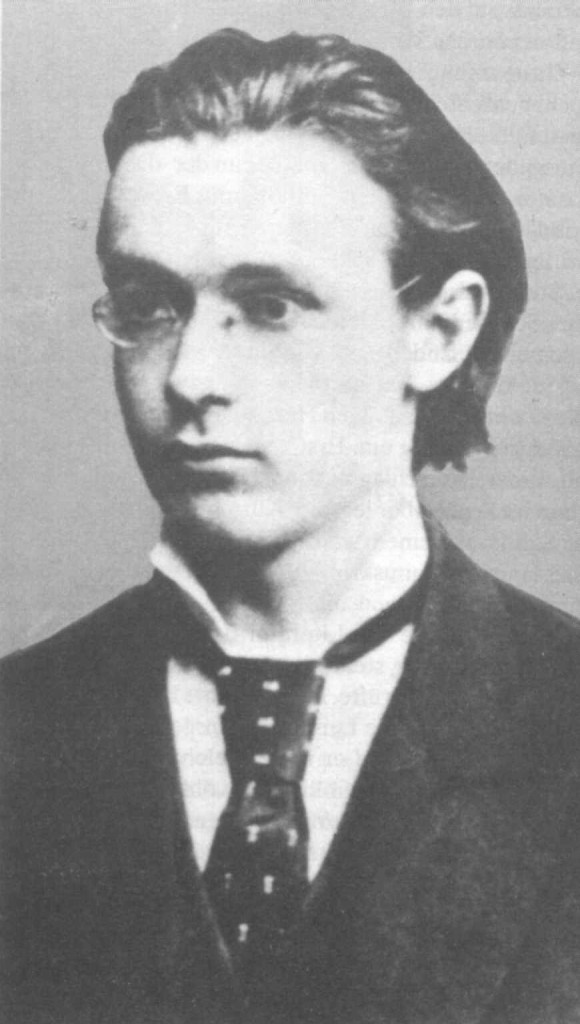

Rudolf

Steiner’s Non-Religious Upbringing

Rudolf Steiner was a child of simple parents (his father was a railroad official at different villages within the Austrian Empire). There was no noteworthy cultural tradition in the household, no books and religion played no role. His father considered himself to be a free-thinker.

However, Steiner already had clairvoyant experiences as boy. In 1913, he describes how as a buy, his aunt (who lived far away) appeared to him in astral shape and asked him for help. When he told his mother, she only said that he was a dumb boy. Only much later did the young Rudolf and his parents learned that she had tragically died, because of suicide. Through such experiences, the boy learned that there is a world “that one sees” and a world “that one does not see”. And he learned to keep quiet about the latter as people simply didn’t understand what he was talking about.

Steiner described later how he, as a boy, already had burning questions about the nature of this world and about life. Finding answers to drove him to devour every book on natural science and geometry he could find. In geometry and math, he found to his delight that there was a kind of ‘world of ideas’ that was grounded in itself without any dependence on the physical world. In this, he saw a similarity to spiritual realities that he was increasingly viewing clairvoyantly.

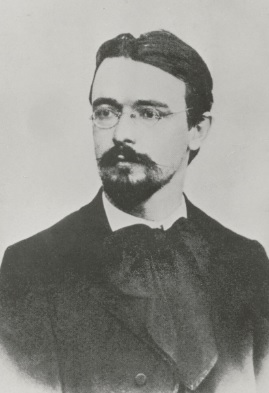

Steiner’s

Views About a Spiritual “World of Ideas”

His interest in science and technology drove him to a study of physics, chemistry, math and biology at the Vienna Institute of Technology. After this, he made a living through the 1880s and 90s as a writer, editor (e.g. of a weekly magazine and as a book editor of J.W. Goethe’s scientific writings) and teacher (e.g. at the Berlin Workers College founded by Karl Liebknecht, an associate of Karl Marx).

In this era, he wrote his fundamental philosophical works, among them Truth and Science (1892, his doctoral thesis on his own epistemology which got him a PhD in philosophy from Rostock University) and The Philosopy of Spiritual Activity which further expanded on this. In these works, Steiner shows how observation of the world (experience) only delivers half of the world, while the other half is gained from a spiritual ‘world of ideas’ in which ideas are ‘observed by the human spirit’ and (scientific) truth is found through permeating the world of observations with ideas to find the inner laws and nature of things. In his Philosophy of Spiritual Activity he defended an ethical individualism, in which a human is the more free and developed, the more he can base his moral actions on ‘intuitions’ that directly emerge from this ‘world of ideas’, instead of a morality that is directed by any authority.

In this era, Steiner regularly criticized the existing Christian denominations because they preached (and often still do) an “otherworldy” Christanity that portrays a spiritual world that is inaccessible to humans as they are dependent on revelation only, e.g. from authority above, while the Christian churches also posited external moral rules that should be enforced on the people. Mainstream Christianity was, for Rudolf Steiner at least, a flight from reality. Everything in him objected to these. That is, next to his later work on e.g. the realities of karma and reincarnation, why the question “Is Rudolf Steiner Christian” is often answered by clear “no”.

It would be wrong to think, however, that Steiner was an ‘atheist’ in this era. For example, in his introductions to Goethe’s scientific writings (which Steiner edited and published in the 1880s) he wrote: “What philosophers call the Absolute, eternal being, the foundation of the world, what religions call God, we call, based on our epistemological discussions: the world of ideas.” And: “If religion teaches that God created man in his own image, our epistemology teaches us that God only guided creation to a certain point. There he created man, and man, recognizing himself and looking around him, sets himself the task of continuing and completing what the primal force has begun.” It is not that Steiner fundamentally rejected the idea of God, just that he – in this phase of his development – interpreted God differently.

A Crisis of the Soul

This resistance against mainstream Christianity and their (quite arrogant) stance that they were only channel through which God reveals himself to the world, and their efforts to enforce their moral views on the masses (which in Steiner’s views really destroyed through morality) led him to become fascinated for years with the works of Friedrich Nietzsche and later even Max Stirner, who drove his individualism to the max.

In his autobiography, Steiner described how his struggle with a natural world that INCLUDED the spiritual, led him to experiencing a world of spiritual entities which he would later call ‘ahrimanic’, who want to instill pure mechanical materialistic thoughts in humans and with which he had to fight. This ‘test of the soul’ led him to a profound spiritual crisis. This ended after a turning point experience – apparently lasting days or even weeks – in which he clairvoyantly viewed the crucial importance of the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ at Golgotha. Steiner would later describe this dramatic experience only once, in a very brief but poignant passage in his autobiography.

The Birth of Anthroposophy

Only after this experience – which happened somewhere in the final part of the1890s – did Steiner began to speak about esoteric subjects and his own clairvoyant views. Before that, he described his spiritual convictions in general, philosophical language without mentioning anything perceived clairvoyantly That is why references to religion and Christianity in his earlier works were sparse.

But from 1900, the huge importance of Christianity and its necessary spiritual renewal in our time became the center of his activities. In 1902, in his fundamental work Christianity as a Mystical Fact he described how ancient religions and mystery traditions (such as in the Greek mystery schools) laid the groundwork for Christ to appear on earth, and made Christianity a “public mystery religion” through – what Steiner called – the “Mystery of Golgotha”, e.g. the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

Such a death and resurrection were, until that moment, parts of hidden mystery initiations that only a few chosen ones could go through on a soul level only in the ancient mystery centers. Jesus Christ made this initiation public and underwent it himself at the physical level – e.g. a physical death and resurrection – and thus evoked the anger of existing religious leaders (until that moment, the penalty for ‘treason of the mysteries’ was capital punishment).

So Is Rudolf Steiner Christian?

Christianity thus is at the core of anthroposophy. But this does not mean that other religions are simply wrong. On the contrary, Steiner’s clairvoyant research showed him that all religions emanated from the single spiritual world in which all humans live, but different peoples at different times needed different views, and therefore the (relative) differences between the religions came into being.

But the Christ figure shows up most religions in some form, e.g. as Krishna in Hinduism, as Osiris in the ancient Egyptian religion and as Ahura Mazda c.q. Zarathustra/Zoroaster in the ancient Persian religion. Steiner maintained that Christ does not care how he is called, that we are only at the beginning of Christianity and not the end, and slowly but gradually the world’s religions would merge into one “Michaelic humanity” of all people of good will. Steiner, for example, maintained that a merging of Christianity and Buddhism had already happened in the spiritual realm and it’s only a matter of time before this would happen among humans on the earthly plane, too. And this is indeed what we perceive today: on the Buddhist side in e.g. the work of Thich Nhat Hanh – often seen as the world’s most influential Buddhist after the Dalai Lama – who wrote books such as Living Buddha, Living Christ (1996) and on the Christian side by authors such as renowned theologian Paul Knitter, who wrote Without Buddha I Cannot Be a Christian (2013).

Anthroposophy, Steiner maintained, is not a religion nor does it replace religion. It is, and wants to be, a ‘science of the spirit’ by systematically researching the (spiritual) world through higher faculties that slumber in each human being and can be developed by conscious effort. This way, any person can gradually begin to have his own higher perceptions and experiences, and become convinced that the spiritual world is real.

Steiner did, however, give advice and counseling to a group of mainly Protestant leaders and a few Catholic Priests on the founding of a new religious community (or church, if you like), called the Christian Community. Steiner wrote a renewed Christian mass and other sacraments for this community, but in all other respects, the Christian Community – which is now present in a dozen countries worldwide – is independent from the Anthroposophical Society. Steiner maintained that probably most people who embraced anthroposophy, would no longer feel the need for any church attendence, but for those who do, the Christian Community is there.

In Steiner's Own Words...

Steiner once summed up the relation of Christianity to other religions and to anthroposophy in this short and insightful way:

"But when religion transfers over into knowledge, when people are no longer given religion in its old form, when they are merely directed by faith to the wisdom that guides evolution, will Christianity then cease to exist? In the future, there will be no other religion based on mere faith. Christianity will remain, for although Christianity was a religion in its beginnings, Christianity is greater than all religion! That is the wisdom of the Rosicrucians. In its beginnings, the religious principle of Christianity was more comprehensive than the religious principle of all other religions. But Christianity is even greater than the religious principle itself. When the veils of faith fall away, it will be a form of wisdom. It can completely shed the veils of faith and become a religion of wisdom, and spiritual science [i.e., anthroposophy] will help prepare people for this. People will be able to live without the old forms of religion and faith, but they will not be able to live without Christianity, for Christianity is greater than all religion. Christianity is there to break down all forms of religion, and that which fulfills people as Christianity will still be there when human souls have outgrown all mere religious life." (Rudolf Steiner, Das Hereinwirken geistiger Wesenheiten in den Menschen, GA 102)

This quote shows how nuanced an answer to the question "Is Rudolf Steiner Christian" has to be.

But What About Karma and Reincarnation?

But what about things like karma and reincarnation – aren’t they contrary to Biblical Christianity? No, reincarnation actually is in the Bible, if you know where to look. It’s not put up front, and the fact that mainstream Christianity has never embraced the idea of reincarnation until his moment, has justification. For if people in past centuries had adopted this, Steiner said, it would have worked against their right moral development.

But this is no longer the case. On the contrary, Steiner maintained, if Christianity would not undergo a fundamental spiritual renewal in accordance with modern consciousness, it would die a slow death. Steiner worked with all his powers to prevent this.

I know this is a controversial topic that needs a much lenghtier treatment, and I will put up pages about this later.